|

© Dr. Artur Knoth |

Brazilian Philately: The Pan Am Zeppelin Flight of 1930 |

Effective Rates for Brazilian Mail on 1930 Flight

The Preparations

This article about the Zeppelin postage rates for letters out of Brazil, just like the article about the stamps issued, is a revised and expanded update of an initial article published elsewhere /1/. The first Pan Am flight of the Graf Zeppelin created and carried an enormous amount of mail, most of which was philatelic in nature. This specific flight was to be a type of rehearsal or proof-of-principle, to demonstrate the feasibility and reliability of a regular schedule of Zeppelin flights between Europe and the Americas /2/. For this reason Dr. Eckener attempted to get along the proposed route, as many postal authorities as possible to issue special stamps. Collector's covers were a major source of revenue for the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH (LSZ), and these stamps would heighten the philatelic effect (pressure)? In the case of the USA completely, and in the case of Germany Dr. Eckener was partially successful. Of the other two, the Argentina had a semi-private issue in that normal airmail stamps were overprinted, whereas the Brazilian part was strictly a private issue of the Syndicato Condor. In both cases, besides the “Zeppelin” part, normal Argentine/Brazilian postage (5 or 12 cents/ 200 to 500 Reis) was required to cover the official part of the postal stream. And exactly here, one would think that even the Zeppelin rates would be fixed at a certain value, and stay valid during the flight. In the case of Brazil, the one notable exception, this was not true.

Initially a set of stamps was issued to cover all the possible postal tariffs for the various planned legs and maildrops of the flight. As the stamps article shows, the lower denominations were quickly sold out, required measures such as overprinting other values and normal Condor stamps. One of the reasons that the first two lower denominations were quickly sold out can be possibly be traced to souvenirs (mint stamps) that many of the German-Brazilians, albeit immigrants or businessmen created as a remembrance of this premier. This could also have been a factor in the creation of the famed “Parahyba” provisional /3/. The “average” Brazilian, with their cost of living/wages, couldn't even think of paying for such a souvenir. In any case, the countries participating with mail on this flight had an announced initial set of tariffs /5-8/.

Yet even the better-off people sent covers on the cheapest routes. In any case, remember that these three denominations corresponde to the 60 cents, $1.20 and $2.40 US (the official US rates). That was a heck of a lot of money in 1930. As an example one need only cite the famous philatelist Herman Herst Jr. /4/ In 1932 he had two different jobs, one paid $15/week for a 60 hour week. Later he received $12 for less hours but that was eventually increased to $15. By 1936 he had reached a whole $28 a week. Fact, someone like Herst, in 1930, would have had to burn almost a week's salary to buy 3 sets of Zeppelins. The situation in Brasil was even worse, even among the middle class. My father-in-law used to go the cinema as a young adult, for a few 100s of Reis, bus fare and refreshments included. Image what value 5$000 Reis then represented. A daily newspaper, national edition, was 0$100 Rs. A simple postcard sent on this flight was thus the equivalent of 50 newspapers.

The Rate Tables

Running up to the flight, there was a great deal of publicity which contained the rates for preparing covers for the flight from several countries published in philatelic journals as well as national newspapers.

Table 1 demonstrates the rates that were initially published in the USA and Germany prior to the Zeppelin flight or enshrined in catalogs that appeared shortly after the flight.

|

Rates Tables/Source |

USPO/German PO |

Von Meister |

F. W. Kummer |

|||

|

Route Leg |

Card |

Letter |

Card ◊ |

Letter |

Card |

Letter |

|

Pernambuco - Rio de Janeiro |

† |

† |

(2$500) |

5$000 |

2$500 |

5$000 |

|

Rio de Janeiro - Pernambuco |

† |

5$000 |

† |

† |

2$500 |

5$000 |

|

Rio de Janeiro - Lakehurst |

† |

10$000 |

(5$000) |

10$000 |

5$000 |

10$000 |

|

Pernambuco - Lakehurst |

† |

† |

(5$000) |

10$000 |

5$000 |

10$000 |

|

Rio de Janeiro - Seville |

† |

20$000 |

(10$000) |

20$000 |

10$000 |

20$000 |

|

Pernambuco - Seville |

† |

† |

(10$000) |

20$000 |

10$000 |

20$000 |

|

Rio de Janeiro - Friedrichshafen |

† |

† |

(12$500) |

25$000 |

10$000 |

20$000 |

|

Pernambuco - Friedrichshafen |

† |

† |

(12$500) |

25$000 |

10$000 |

20$000 |

|

Footnotes |

◊ |

Cards are exactly half of the letter rate |

||||

|

† |

Not mentioned or rates not expressly stated |

|||||

Table 1: Comparison of supposed rates for covers on this flight initially

The sources are as follows:

|

USPO/German PO |

/5,8/ |

These rates were published in a USPO bulletin and repeated in the German equivalent. |

|

Von Meister |

/6/ |

Taken from the advertisement published in the Airpost Journal. |

|

F. W. Kummer |

/7/ |

Out of his 1931 book |

Taking a look at the Mish-Mash of rates contained in Table 1, one notes a few interesting aspects:

1) In any case, at least in terms of the intended rates during the planing of the flight , the von Meister rates are to be taken the most seriously. This stems from the fact that von Meister was (as announced in both the ad and the USPO circular) the official agent/representative of the LSZ in the United States of America.

2) Some of the postal card rates are rather strange. Since no 2$500 stamp was issued, how was a person to frank an intra-Brazil card or a post card to Friedrichshafen and/or beyond? So even the von Meister rates, albeit the most reliable of all, demonstrated either lousy planning or at best a state of confusion on the part of the planners.

3) There were weight limits on the letters, i. e., in the USA only letters up to 1 oz. /5/ were allowed. In Germany the weight could not exceed 20 grams /9/. Thus, no overweight letters were allowed. At least from this countries. We'll see that the clocks in Brazil ticked differently.

4) No matter which of the rates you look at in Table 1, the letter rate for the USA never exceeds 10$000. Looking at rates for Spain and beyond, you can understand the issuance of the blue 20$000. But if only simple letters and cards were allowed, why was a part of the 20$000 stock overprinted with the “Graf Zeppelin” and “USA” covering the Europe? There was absolutely no reason for this version of the stamp, or was there?

The Brazilian Rates Carnival

After having gone through the theory, what did actually occur? Viewing a selection of different covers in several categories demonstrates how contradictory the evidence can be. At this point, I would like to note that when it comes to some definitions, whether a card really flew, whether a souvenir that never really entered the mail stream officially and many others that some people define as authentic covers, I tend to be a reactionary conservative, even when the “experts” are of a different mind.

A. No Zeppelin Postage

Weird as this may seem at first glance, there are a lot of covers on this flight that can fall under this category. We've already mentioned that technically the inland rate (Rio to Pernambuco, Pernambuco to Rio) for a card was 2$500, yet no such denominated Zeppelin stamp was supplied. Figure 1 demonstrates a typical Owen cover of which there are quite a few.

The card in Fig. 1a has the number 51 in the lower left corner and this (together with further numbered examples ) leads to the conclusion that there are probably 60 or more of these covers total. The postage on the card is 2$600, seemingly 2$500 for the Zeppelin part and the 0$100 for the official Brazilian Post Office (BPO) rate for inland cards. Note: there is no Zeppelin stamp. I doubt whether the BPO reimbursed LSZ for the revenue represented by the 2$500 in Brazilian stamps on this cover. And remember, with about 60 of them, this “Owen” lot represented a possible $20 in revenue alone (a non trivial sum for the time). Note that the displayed Owen cover was actually canceled with the Condor cancel. Other Owen covers for the Pernambuco-Bahia leg are found canceled instead with a BPO device. Contrary to the opinions of experts, I'm not convinced that these covers were actually transported on the Zeppelin, nor that they deserve the high value given in the latest Michel as 64 Bd and 65 Be /9/; for me these covers are oddities or even a Spielerei, that Condor let go through, as a courtesy to the collector.

Another Zeppelin-less group consists of the crew and/or passenger on board souvenirs created during this flight. Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate examples of these. In these cases, only BPO 0$300 stamps are present. In Fig. 2, the BPO cancel was used and the larger Recife Condor cancel/cachet was applied as the latter. In the case of Fig. 3, the Recife device was also the cancel. Note that the reverse of neither of these cards are any even slightest further postal markings on them. These were obviously, hand-back souvenirs. One also sees these type of covers, without the BPO postage: instead the 5$000/1$300 stamp is used and has the Recife cancel.

Now we come to a true oddity, the cover displayed in Figure 4. Anyone familiar with the covers of this flight will have seen several “Citret” covers. Usually the Zeppelin stamps was applied right next to the Brazilian stamps, or underneath. And the BPO stamps and the Zeppelin were canceled with a Condor device. Here, the only Zeppelin-like stamp is the 5 pfennig blue “Eckener stamp” (Sollors #435 /10/). While the corner where the this stamp has been placed seems to have suffered water/coffee damage, the lack of any additional Condor cancel or one demonstrating that a stamp is missing, can be found. This cover, in hustle and bustle, probably didn't end up being stamped correctly in the Rio Condor office and just slipped through. The reverse has all the needed receiving marks including the arrival cancellation (small circle) of Friedrichshafen as well as the German Berlin L2 airmail cancel (Figure 5).

Figure 4: An example of a

Citret cover without any “official” Zeppelin postage on it

Figure 4: An example of a

Citret cover without any “official” Zeppelin postage on it

B. The Zeppelin Covers

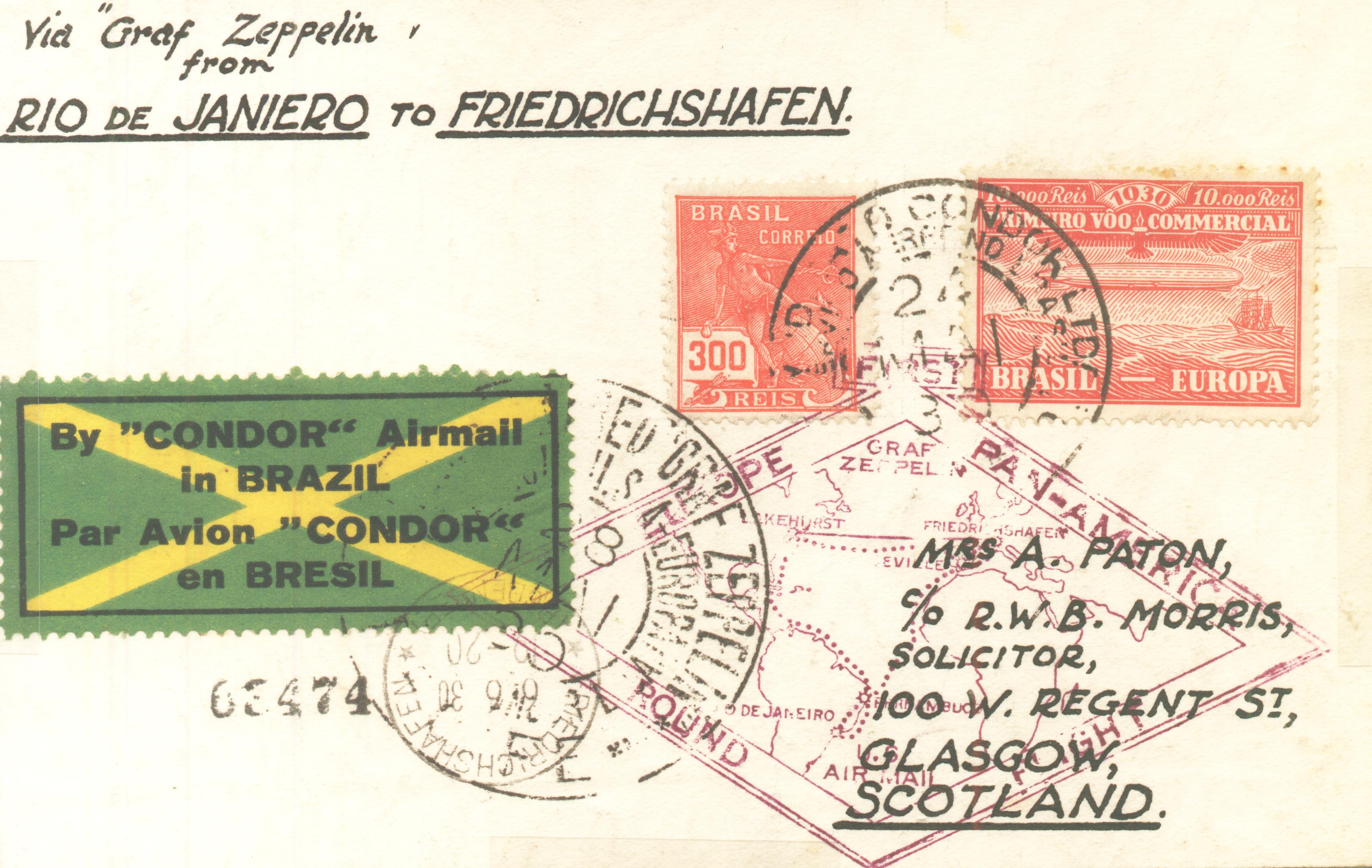

Table 1 demonstrates that in terms of covers to North America, there is no real problem, 5$000 for a postal card and 10$000 for a letter. The rates to Europe and beyond are the ones that show a terrific amount of variation. We'll limit the discussion to the European destinations after Seville, using letters and cards to Great Britain as the examples of the variations possible. Figures 6 and 7 display examples of covers (postal card and letter respectively) with the franking according to the von Meister scheme, except that the theoretical 12$500 postal card rate already was covered with only a 10$000 stamp.

Fig. 6: Postcard to Scotland

franked with 10$000 (von Meister # 03474).

Fig. 6: Postcard to Scotland

franked with 10$000 (von Meister # 03474).

Fig. 7: Typical letter

franking 59AC (A=5$000, C=20$000) for the 25$000 rate.

Fig. 7: Typical letter

franking 59AC (A=5$000, C=20$000) for the 25$000 rate.

The card in Figure 6 as well as the envelope in Figure 7 are both out of an extensive set of covers prepared by J.A.D. Paton with correspondence on all the major legs of this flight. The card has the “von Meister”/11/ number (03474) and the letter in Figure 7, the number (03475). Since the numbers on this flight would eventually reach 30,000, this correspondence arrived fairly early in the game at von Meister's agency.

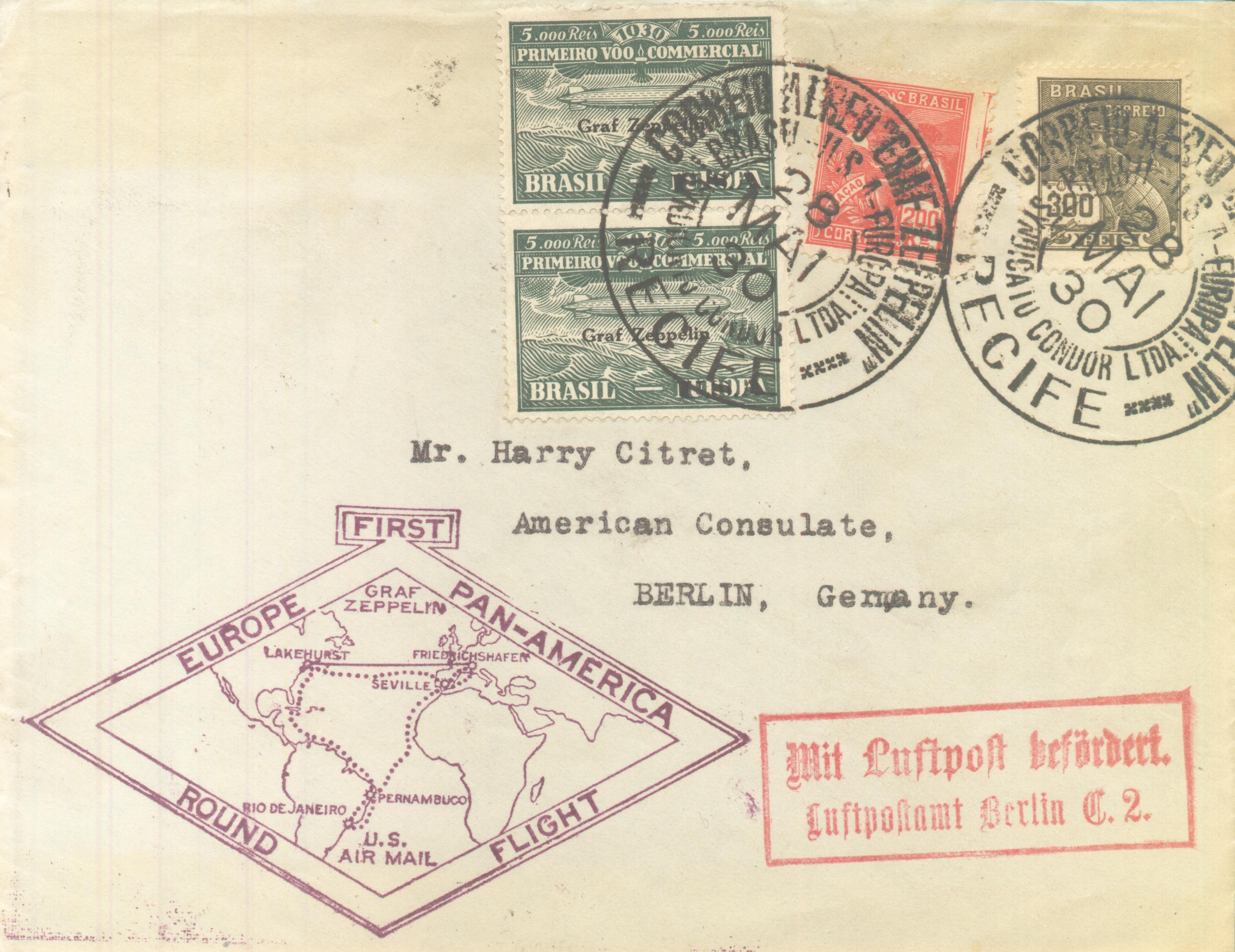

The card in Figure 8 was prepared by a prominent local dealer, Costa & Filhos in Rio, and went for half the rate as compared to the previous card to Scotland. And Figure 9 shows a letter sent to Berlin for only 40% of the supposed correct rate for letters to Europe, as Figure 7 is such an example. The Citret letter demonstrates another oft mentioned fallacy when lots are described at auctions. Although at the behest of Brazilian authorities, the use of the USA overprints only on mail destined to North America was not binding. Nor are such usages that seldom, that they should be considered extra valuable. (Sorry, I can't repeat it often enough). The fronts of both latter covers (Figs. 8 and 9) also display the arrival marks (Friedrichshafen and Berlin C2) that verify there correct passage on the Zeppelin. So what happened here, was that mail was being sent from Brasil to Europe as if the rates for the USA applied.

Fig. 8: Postcard to

Liverpool franked only with a 5$000 stamped

Fig. 8: Postcard to

Liverpool franked only with a 5$000 stamped

Figure 9: Letter to Berlin

franked with a vertical 5$000-USA pair for 10$000

Figure 9: Letter to Berlin

franked with a vertical 5$000-USA pair for 10$000

C. The Local Realities

To be able to find a possible explanation one needs to consider a few relevant facts:

The covers to be serviced by von Meister, had to have arrived the latest by Saturday the 26th of April, 1930/6/. Thus shortly after that date, at least the number and extent of the covers being sent by American collectors was known. The numbers of this flight extend to approx. 31,000/11/. But this total included mail for German, Spanish and Brazilian franked covers. Yet the number of Brazilian franked covers carrying these typical numbers is still enormous and meant that quite a large fraction of the stamps to be issued by Condor in Brazil were “already taken”. This probably was the cause of having the provisionals 5$000 and 10$000 on 20$000 being prepared to be able to handle the volume of mail coming out of the USA. Consider two examples of von Meister covers to see what the situation was as the covers arrived and were being serviced in Brazil.

Fig. 10 demonstrates two very interesting aspects. Although von Meister was the official US agent for LSZ, he used USA-overprinted stamps for a cover to Spain(Europe). Thus, the myth about such a franking not being allowed is exactly that, a myth: at the end of the day, pragmatism ruled. Question, were either the normal (European) versions of the 10$000 and/or the 20$000 already then in short supply?

![]() Figure 10: A von Meister

(#25290) cover Rio-to-Spain at 20$000 rate.

Figure 10: A von Meister

(#25290) cover Rio-to-Spain at 20$000 rate.

The next cover shows how dramatic the situation might have actually been. Consider Fig. 11: just three von Meister numbers later (25293) and already the franking has been done using a mix of the 10$000 USA-overprint and a 10$000/20$000 provisional to be able to complete the 20$000 Spanish rate.

![]() Figure 11: A von Meister

(#25293) cover Rio-to-Spain at 20$000 rate.

Figure 11: A von Meister

(#25293) cover Rio-to-Spain at 20$000 rate.

While doing research on the Zeppelin “Parahyba” provisional, the famous large “5” on a 20$000 /3,12/, I came across an interesting ad in a newspaper/13/. In previous research, perusing Brazilian philatelic journals of that time, I'd never discovered an ad such as von Meister ran in the equivalent Airpost Journal in the US. Yet now, going to the Brazilian National Library to find material about the Parahyba provisional, I found a newspaper, a daily that also does the official publication of government business for the state of Parahyba do Norte. Beginning with the May 5th, 1930 issue, Condor started running a special ad, different from the one used to advertise its airmail service, that announced the carrying of mail on the upcoming Zeppelin flight. It also announced the issuance and sale of special stamps for the flight and contained a table of the rates for correspondence to be sent on the flight (Table 2) that differed dramatically from the other published rates for mail to Europe. But the real surprise is what was stated in the brackets after “letters”. The (...) was (...até 10 grammas), which means for letters up to 10 grams. This means that perhaps overweight letters were allowed. Condor, together with LSZ, made a big push to get business mail, which was often much heavier than the standard letter. It also indicates that the local weight limit was lower than those of the other countries where 20 grams and one ounce were accepted. Not only that, but the announcements in Germany and the United States expressly state that the mail may not exceed these single weight limits! A further report, in a contemporary philatelic journal, has the same information embedded in a verbose review of the stamps and the flight /14/.

|

Local Brazilian Rates |

Condor |

BPO |

|

|

Americas |

cards |

5$000 |

0$200 |

|

letters(...) |

10$000 |

0$300 |

|

|

Europe |

cards |

5$000 |

0$300 |

|

letters(...) |

10$000 |

0$500 |

|

Table 2: The actual published Syndicato Condor do Brasil rates.

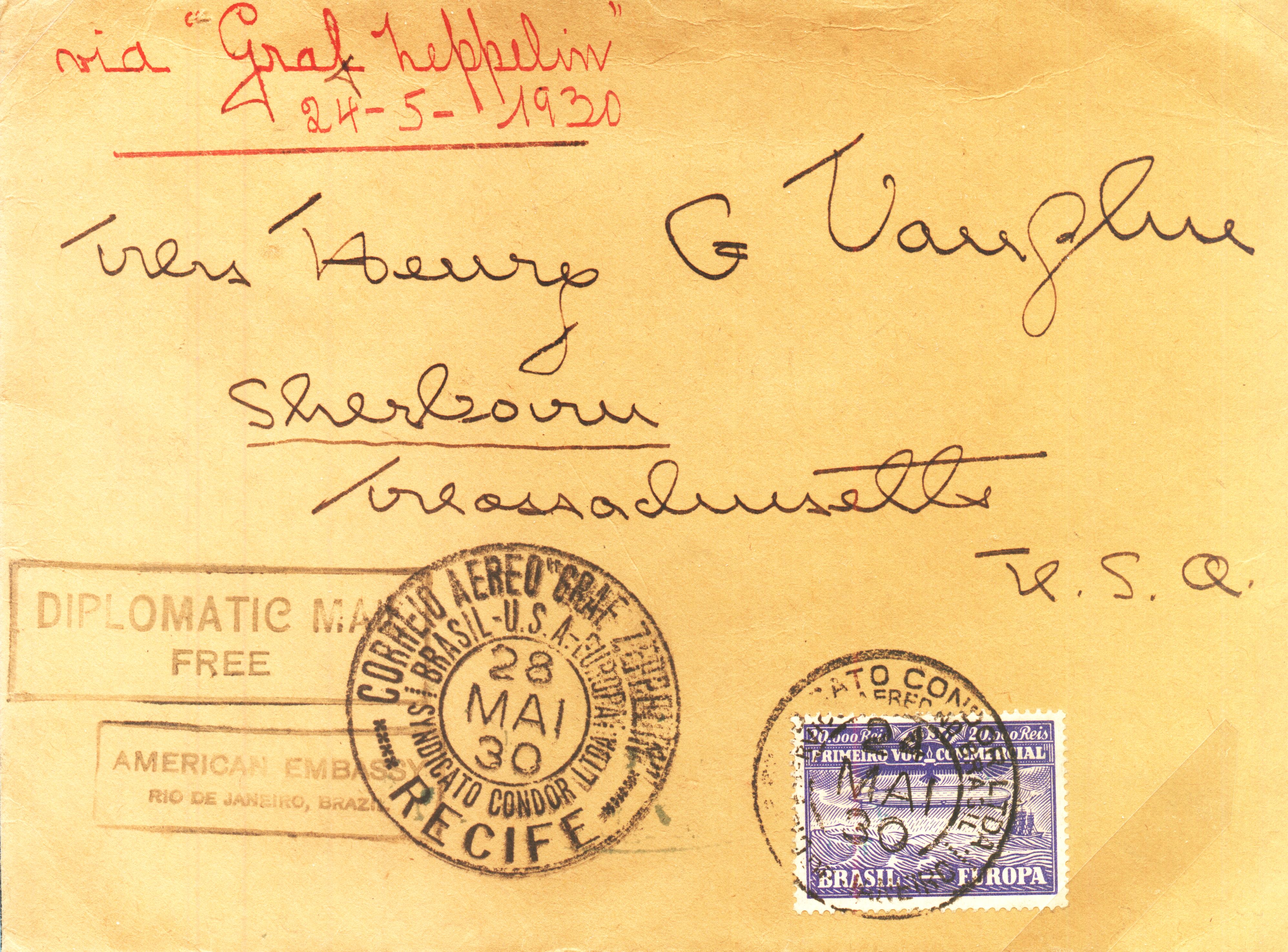

Technically, one cannot prove whether an envelope sent on this flight weighed more than the stated 10 grams without the contents, or a special weight marking. But there are indications that overweight mail existed and was conveyed on this flight. Figure 12 provides a nice example, that I initially used in my FFE8 article /1/. This cover has a lot of interesting aspects that have been dealt with already in another article/15/, but the main one being that the heavy craft paper envelope alone is a little heavier than 10 grams. With the rates in Tab. 3 one could interpret that this is simply an overweight letter and the 20$000 is the correct rate for this letter.

Figure 12: Envelope out of

heavy craft paper that alone weighs 10 grams.

Figure 12: Envelope out of

heavy craft paper that alone weighs 10 grams.

This new aspect can help to explain a few exotic covers one sees on this flight. One sees a few covers where the franking seems to be way too much, but it doesn't, at the same time, seem to be a philatelic cover, the type where a complete set of stamps was used as the franking. One sees often letters to Europe that have 30$000 (usually a 10$000 plus a 20$000). On the one hand, this could be franked to fulfill the initial 25$000 rate and no 5$000 was handy. But now it could also be a doubly overweight letter franked according to the local, Brazilian rate. There even exists a cover to the US with 40$000 (2x10$000+20$000) whose envelope has a letter card that could indicate a business address and a heavier letter. Even the initial rate to the US was only 10$000, i. e. this letter has four times the normal frank and represents $4.80 in US$, not trivial by any means. This latter explanation, in light of these new facts, now becomes a viable possibility.

And a recent acquisition has really cemented the case for heavy business letters. To use the hyping vernacular of the present epoch, this could be the mother-of-all-commercial-covers on this flight. Although this cover and some of the stamps are in miserable shape, the cover is a true gem (Fig. 13 and 14).

![]() Figure 13: 8 times the

normal weight cover for 80$000

Figure 13: 8 times the

normal weight cover for 80$000

![]() Figure 14: Back of cover

with staple marks

Figure 14: Back of cover

with staple marks

The cover in Figures 13 + 14 has several features that validate the conclusion that this was solely a commercial communication whose monetary importance justified the horrendous sum expended in postage fees. Consider the following aspects:

Postage: The four 20$000 USA-overprinted stamps would pay for a letter up to 80 grams in weight, as far as the Zeppelin is concerned. Remember, that this represents over $10 in postage, a sum with which very few people could afford to make a joke cover. The BOP part could be calculated as 300 reis for the first 20 grams (rate for letters to North America) and 200 Reis for each additional 20 grams. Thus, the Brazilian postage for 80 grams would be 300 + 3x200 = 900 Reis. The envelope is franked with a 200 Reis red aviation stamp and a 700 Reis violet Mercury stamp, exactly 900 Reis as required. An additional factor is how the expensive Zeppelin stamps are attached to the cover. The typical dark, molasses-like glue found everywhere at the time was utilized to ensure the stamps stayed on the envelope. No philatelist in his right mind would ever even think of using something of this sort, a businessman, on the other hand, wants to be sure that his $10 don't get lost during transit and end up with postage due.

Address: The letter card on the envelope and the preprinted address, with a rubber stamp to indicate the agent, are very typical for a business letter. This is just an educated guess, but all things considered, this letter could easily have dealt with something in the automotive industry, since Detroit was the automobile center of the USA at that time.

Potpourri: Two other factors lend interesting clues. The envelope was opened on the right edge, typical for envelopes in business that contain a wad of documents, and were thus extricated. The damage to both the envelope and the stamps (their placement as well as by opening) show that no regard was made as to a possible philatelic cover to be preserved. Another very telling factor is visible on both the front as well as the back of the envelope. In Figure 13, to the left of the stag's head and antlers, two small holes, the type a staple makes, are visible. In Figure 14, the corresponding holes are visible in the upper right hand corner.

Taking all these indications in their totality together, one would seem more than justified in seeing as truly and solely commercial cover.

Conclusion : The Rates : The Real Thing

Table 3 represents the distillate of several hundreds of comparison covers and observations of many years. The basic conclusions can be summed up in three main conclusions:

|

The Real Rates |

Initial (von Meister) |

Local (Condor) |

||

|

Route Leg |

card |

letter |

card |

letter(...) |

|

Pernambuco - Rio de Janeiro |

5$000 |

5$000 |

||

|

Rio de Janeiro - Pernambuco |

5$000 |

5$000 |

||

|

Rio de Janeiro - Lakehurst |

5$000 |

10$000 |

5$000 |

10$000 |

|

Pernambuco - Lakehurst |

5$000 |

10$000 |

5$000 |

10$000 |

|

Rio de Janeiro - Seville |

10$000 |

20$000 |

5$000 |

10$000 |

|

Pernambuco - Seville |

10$000 |

20$000 |

5$000 |

10$000 |

|

Rio de Janeiro - Friedrichshafen |

10$000 |

25$000 |

5$000 |

10$000 |

|

Pernambuco - Friedrichshafen |

10$000 |

25$000 |

5$000 |

10$000 |

Table 3: The “effective” initial rates and the later modified local rates on this flight.

1) The von Meister mail, to the greatest extent, followed the rates as they are in Table 3. Yet, even for von Meister franked mail (i. e. those covers carrying the characteristic five digit von Meister number /11/) there are variations that follow the local reduced values. And it would seem that the chronologically of the numbers is no guide to the variants. It would seem that as each group of covers arrived at the New York office they received their numbers, but the actual servicing of the covers, applying stamps and cancels was due in Brazil on the pooled covers as a single batch for a given route destination.

2) The local mail, especially that of local dealer prepared covers, usually followed the local rate table. Any exception to this rule usually represents a philatelic motivation, e. g. covers with complete sets etc..

3) That covers sent from Brazilian addresses can, in some cases, be correctly franked with much more the the basic rate and thus represent overweight letters.

In any case, as anyone knows all too well you has lived in Brazil, in the case of the local rates, the economic interests of Condor and the Brazilian penchant for the “jeito” met and were victorious.

References:

/1/ Dr. Artur Knoth; Condor do Brasil Zeppelin Covers on the !st Pan am Zeppelin Flight of 1930 - “The Rate Samba”; FFE-Journal #8, 121 (May 2005)

/2/ Dr. Hugo Eckener: Im Zeppelin Über Länder und Meere - Der Südamerika-Dienst; pp 281-352 (Verlagshaus Christian Wolff, Flensburg, Germany – 1949)

/3/ Wolfgang Maassen: Rätsel um das Parahyba-Provisorium Brasiliens; Philatelie 56(269), 37 (August 2004)

/4/ Herman Herst Jr.: Nassau Street; page 3 (Amos Press, Sidney, Ohio 1988)

/5/ W. Irving Glover: “Graf Zeppelin” Europe-Pan America Round Flight; USPO Bulletin 59102° US Government Printing Office and also repeated in the Amtsblatt des Reichspostministeriums Nr.36 (29 April 1930)

/6/ Von Meister: Special U.S. And Foreign Stamps etc.: Ad in the Airpost Journal of May 1930

/7/ Dr. Victor M. Berthold & F. W. Kummer: Handbook of Zeppelin Letters, Postal Cards and Stamps, 1911-1931; page 48, (1932 Edition - I. Gomez-Sanchez New York 1931)

/8/ Amtsblatt des Reichspostministeriums Nr.33 (19 April 1930)

/9/ Michel Zeppelin- und Flugpost-Spezial-Katalog 2002

/10/ Kuno Sollors: Nichtpostalische Flugmarken Katalogisierungen ~ Teil 7, 1973

/11/ Artur Knoth: Early Zeppelin Covers Bear von Meister Numbers; Linn's Stamp News 75(3846), 28 (July 15, 2002)

/12/ Donna O'Keefe: Linn's Philatelic Gems II - The Rarest Zeppelin; page24 (Amos Press, Sidney Ohio 1985)

/13/ A União #101, 6 (4.5.1930)

/14/ Graf Zeppelin; O Philatelico #53, 5 (6/1930)

/15/ Dr. Artur Knoth: Airmail Goes Diplomatic; Airpost Journal 75(4), 137 (April 2004)