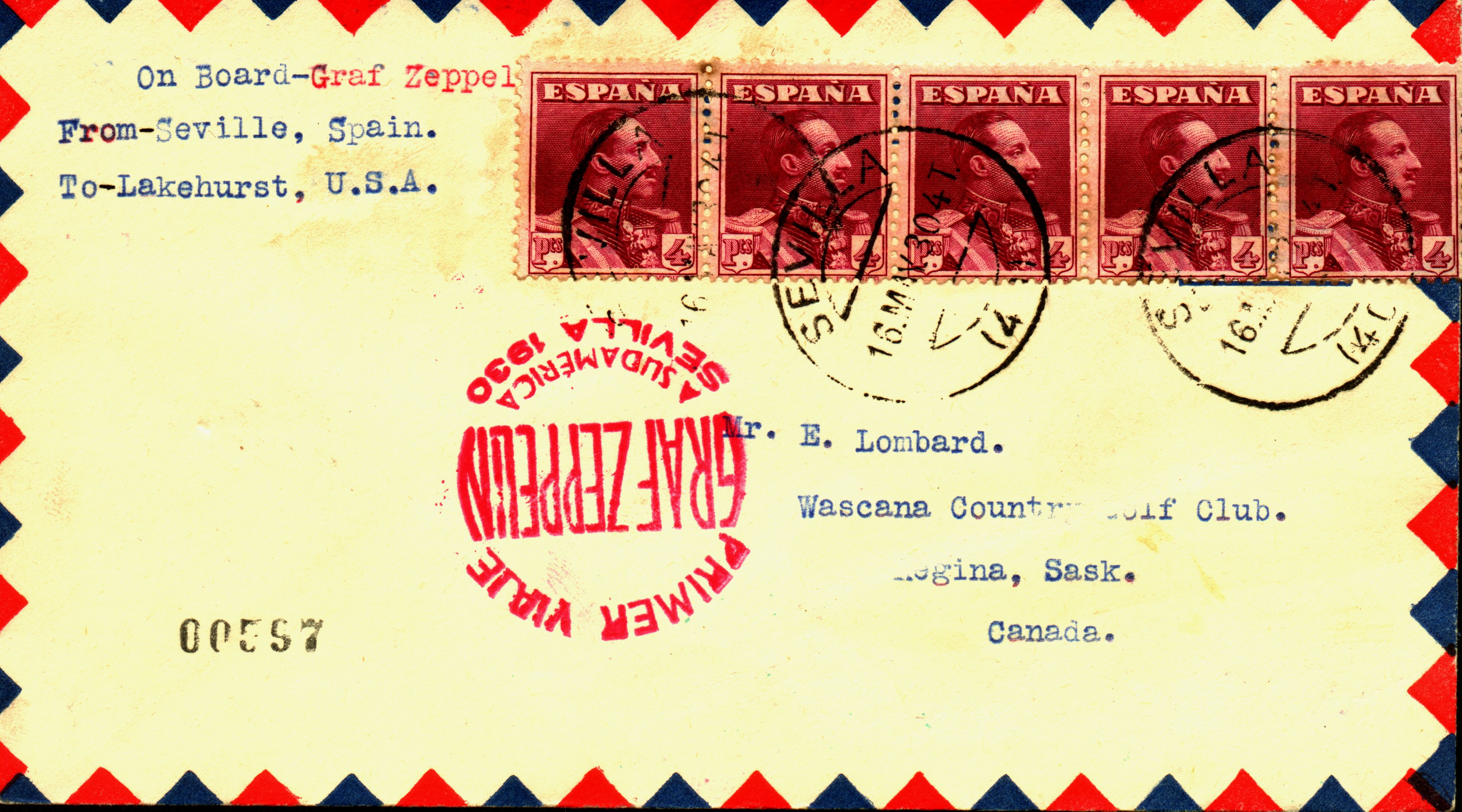

Fig.1: Spanish Pan Am cover

(Sieger #58) with the number 00597

Fig.1: Spanish Pan Am cover

(Sieger #58) with the number 00597

|

© Dr. Artur Knoth |

Brazilian Philately: The Pan Am Zeppelin Flight of 1930 |

Zeppelin Covers and Those 5 Little Numbers /*/ I. Introduction

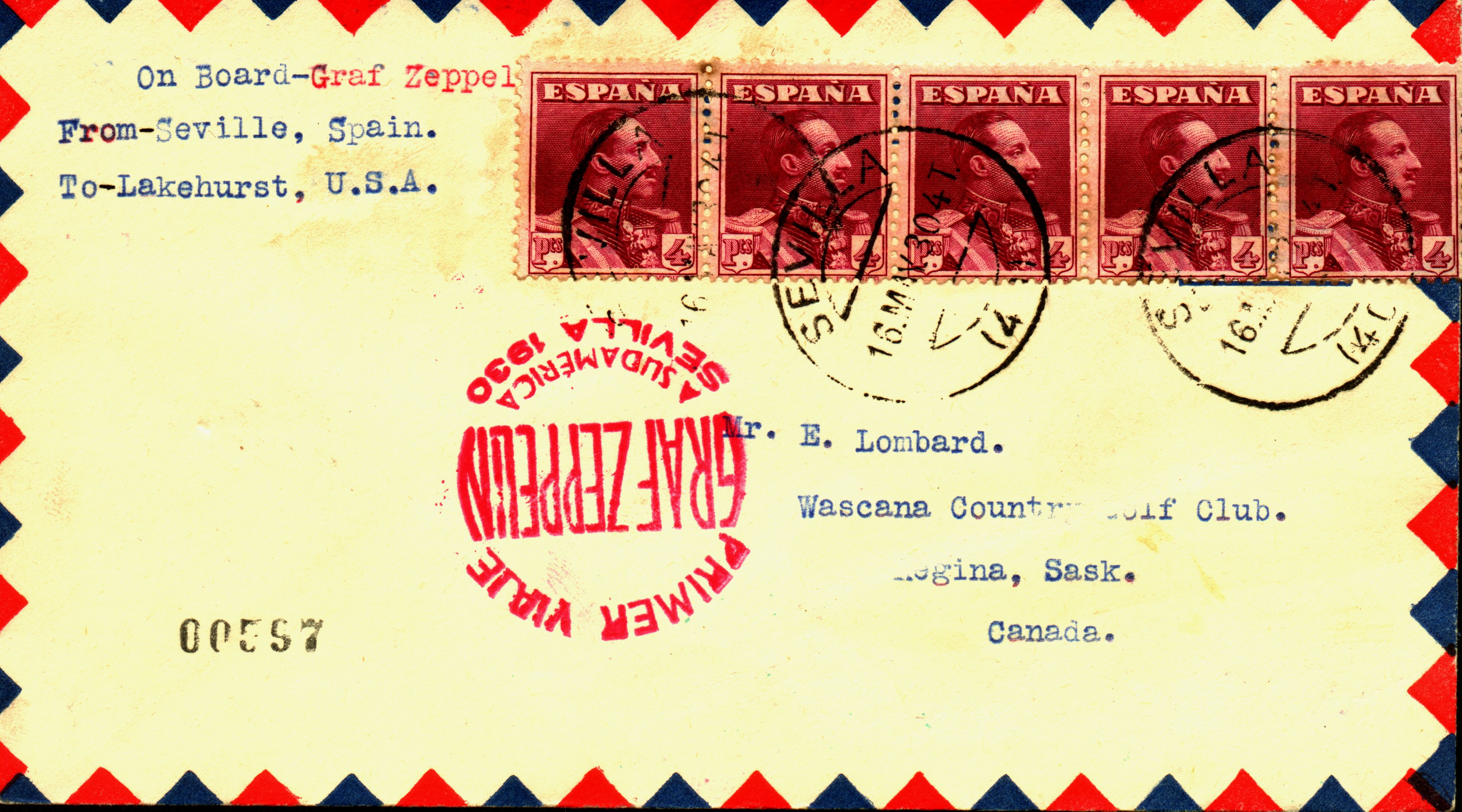

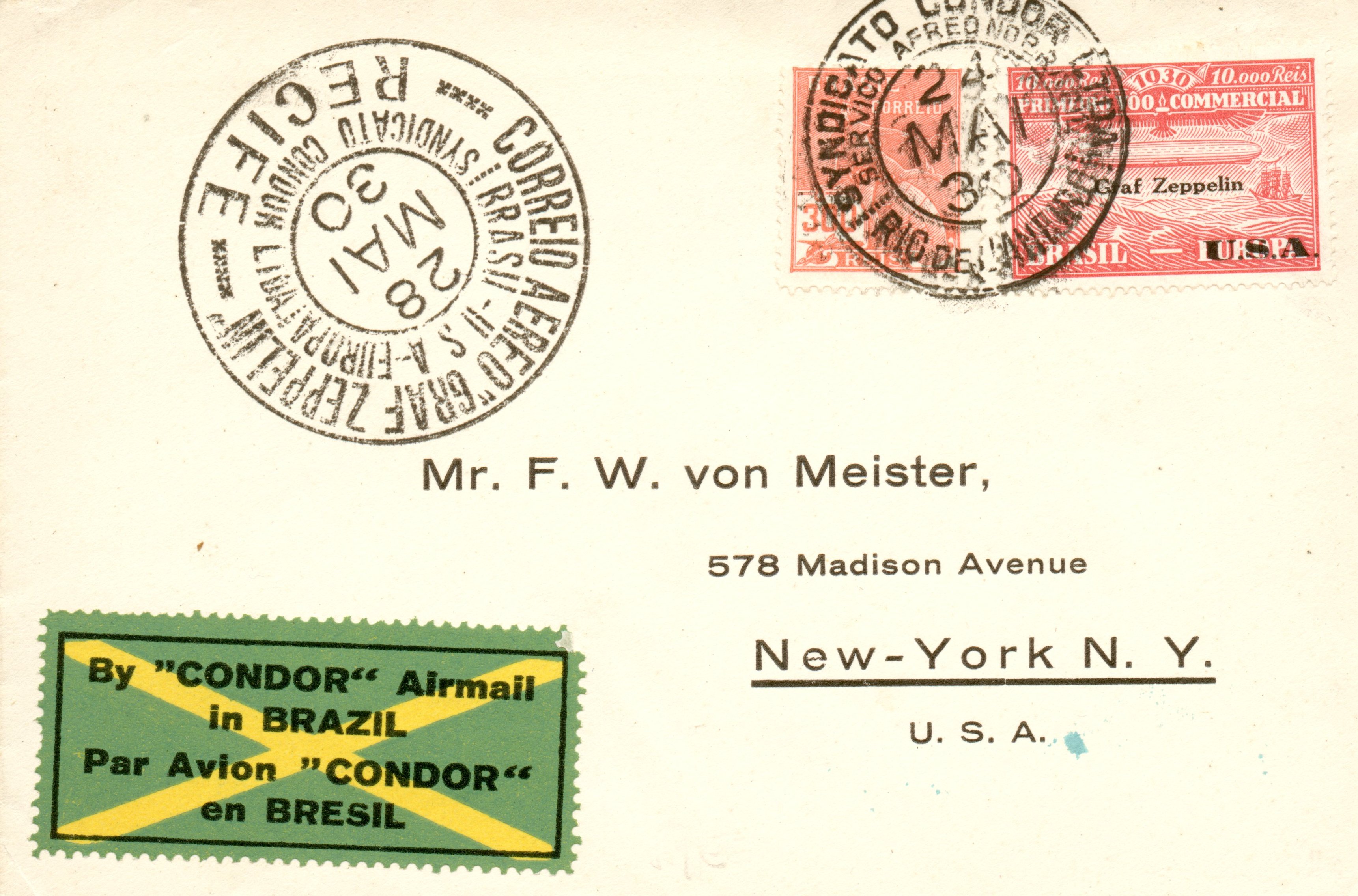

Take a look at any random batch of Zeppelin covers from the years 1930 and 1931, and inevitably you will find a few that have a row of five little black numbers on the front (Fig.1. #00597), usually in the lower left quadrant. For an unknowing general collector, one could easily come to the conclusion that these digits represent some sort of an official postal registration number (and this has led to a case of a semi-forgery, as is presented later on in this article). Even more knowledgeable collectors as well reputable auction houses can fall into this trap. The numbers are "registry" numbers, but not official postal registration numbers. As a confirmation, consider the cover in Fig.2. Clearly written in the upper left corner is the word "registrado" (return addresses of these types of covers often carry Buenos Aires and Chile as return addresses). Yet nowhere is there a registry number to be seen. The answer is that in the early years, the Zeppelin was not allowed to carry anything but simple mail, neither registered nor insured.

Fig.1: Spanish Pan Am cover

(Sieger #58) with the number 00597

Fig.1: Spanish Pan Am cover

(Sieger #58) with the number 00597

Fig.2: Pan Am cover stamped

with a "Registrado".

Fig.2: Pan Am cover stamped

with a "Registrado".

Up to 1932, most Zeppelin flights were singular affairs, a one time only special and/or test flight. They generated a hell of a lot of publicity and a storm of collector interest. Only in 1932, when "scheduled" flights to South America occurred on a regular basis, do you see covers that are truly registered, in the postal sense. To see why this "regularity" was so important and why there are no registered covers for the previous years, one can tap an interesting source. The Brothers Senf, located in Leipzig, were famous dealers who also edited the "Illustriertes Briefmarkenjournal" twice a month. Due to collector inquiries (complaints?), Senf wrote a letter in 1931 to the "Reichspostministerium" asking why registered letters were not allowed on the current Zeppelin flights. The official answer was then published in a 1931 issue of the Journal (/1/). Basically the reply contained the following points:

- no regular scheduled flights (i. e. flight timetables with fixed dates and routes)

- mail drops (often done on this flights, the mail pouch was dropped from the Zeppelin without landing).

What the PO ministry really wanted, was being able to tell when the mail went, on which flight, to where. And when the mail arrived at its destination, that a PO official of the that country would sign-off on the sack (this, by the way, being a UPU regulation). The German Reich's PO would have to pay for any letters lost on drops and/or not countersigned at the destinations. Bureaucrats are the same everywhere (though maybe worse in Germany!). (Here I even wonder how much the Hindenburg disaster cost in terms of lost registered mail?).

II. Background

So what are these numbers, who's responsible for them and since when (and until when) were they used. To answer these questions, one needs to see the situation of the Zeppelin in 1930. After the great success of the around the world flight of 1929, the number of Zeppelin collectors was growing rapidly beyond the initial circle of aero-philatelists. It's an open secret among Zeppelin collectors that the most revenue on any flight came from the, guess who, yes, the collectors. Without the crazy Zeppelin collectors filling the coffers, the company would have had to soon file for the equivalent of Chapter 11. Even though the Zeppelin carried passengers, and at exorbitant rates, it was the collectors who helped pay the bills (sounds all too familiar, doesn't it?). That's why Dr. Eckener tried to get the countries (in the case of the 1930 Pan Am flight) to issue special stamps, to fuel the cover business even more. Just using the numbers of cards and letters sent from the Americas (North and South) and assuming a similar amount for the German covers, the flight had revenues, minimum, of way over $100,000 (1930 dollars that is!). This had become a big business. That meant that you needed agents along the stops to facilitate things. That also meant that, by having agents who helped collectors to get their cards and letters on the flights, the philatelic revenue could be increased even more. This agent in the US was Mr. F. von Meister, and that is why these numbers are called von Meister numbers.

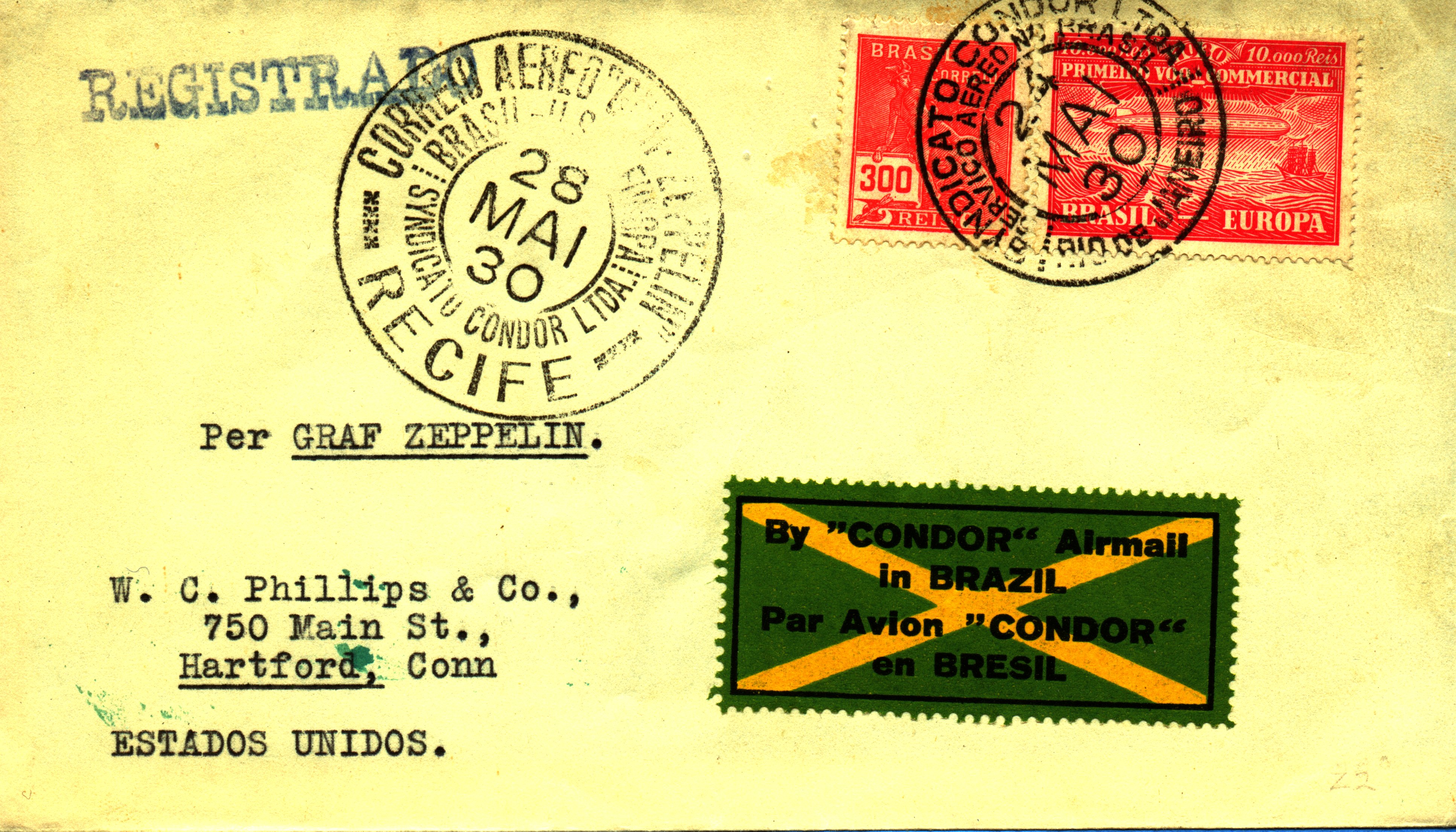

III. Zeppelin Agent von Meister

An official circular posted at the post offices all over the US in 1930 (/2/) even mentions that if a collector wants to get flight covers with German, Spanish and/or Brazilian franking, he can send them with the payment to von Meister in N.Y. City. The circular also mentions, in bold type, "Registered mail will not be accepted for this flight". This is the same von Meister who was the official agent of Zeppelin company and the one responsible for a lot of the dealer created mail of this flight. Note a typical von Meister cover in Fig.3, that seems to have been printed by the same printer as for Sieger and many other German dealers. (actually they all were).

Figure 3: Typical von

Meister cover, here a Sieger #59E

Figure 3: Typical von

Meister cover, here a Sieger #59E

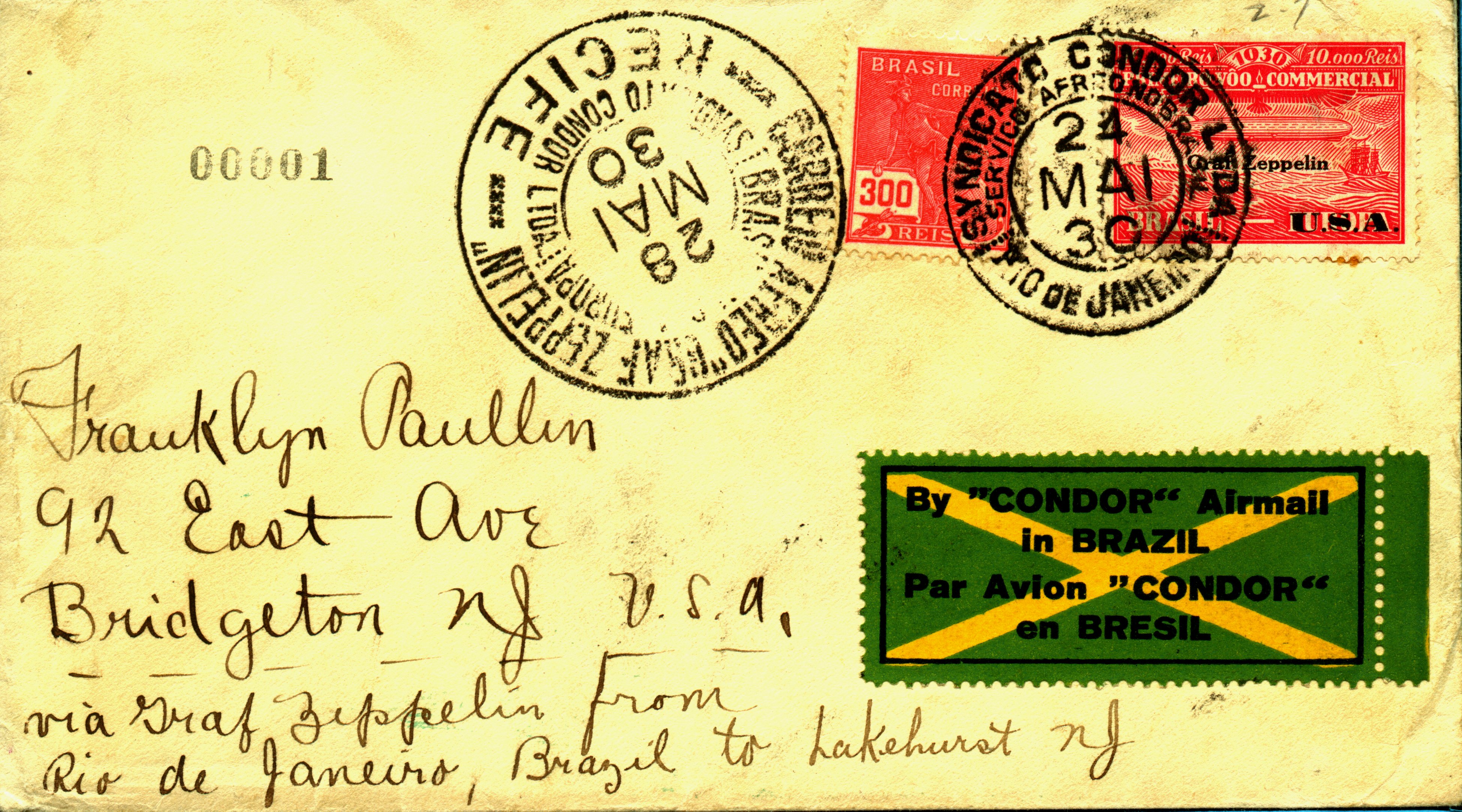

The appearance of these "von Meister" numbers (vM#s) started with the 1930 Pan Am flight (see Fig.3). The cover in Fig. 4 is franked with a Brazilian stamps (500 Reis) and a private Zeppelin stamp franking for the Pan Am flight and carries the number 00001! (Fig. 4a is an enlargement of the number to able to see it more clearly). The practice continued until the Polar flight of 1931. Figures 5 through 12 showed a selection of the cachets for those flights, where one finds von Meister numbers on US collector's covers /3/. It seems that these numbers were placed upon the covers to keep track of the submissions, thus a sort of "registry" number.

Figure 4: Brazilian Pan Am

cover with the von Meister number 00001

Figure 4: Brazilian Pan Am

cover with the von Meister number 00001

![]() Figure 4a: Enlargement of

number, most number impressions are weak due to the envelope paper

Figure 4a: Enlargement of

number, most number impressions are weak due to the envelope paper

The numbers for the Pan Am flight begin with 00001 and the highest I've seen up to now is a cover with # 30851. For the last flight - at least it seems so - that had these numbers, was the Polar flight of 1931 (Fig.12). In this case the numbers begin around 50000 and the highest I've seen so far is 54830. After that it seems to stop.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 5: German Pan Am cachet |

Figure 6: Spanish Pan Am cachet |

Figure 7: US Pan Am cachet |

Figure 8: Northland flight |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 9: Russia flight |

Figure 10: Baltic flight |

Figure 11: Holland flight |

Figure 12: Polar flight |

A possible explanation for the origin of the application of the numbers could be found in American Law. In many criminal cases, where other evidence was lacking, the US Federal government often used the “Mail-Fraud” statutes for a conviction. Perhaps von Meister needed to register in accounting books the covers and payments he received (mainly through the mail) for the services he was offering. Just a mundane fact, mail fraud, that was used against mafia, bootleggers and pyramid schemers could be applied against von Meister, if some customers were to complain. He needed to be able to account accurately for everything.

IV Philatelic Mail

One point in this case is now obvious, no matter how non-philatelic a cover may look or seem to be, if those five little black digits are on it, it is philatelic mail. This mail was prepared by collectors and sent to von Meister for further transfer to the specific countries to be franked and sent. Real business letters actually exist for the 1930 Pan Am flight (a subject for a future article), but perhaps as much as 99 and 44/100 % of the mail, or more, was philatelic, prepared by dealers (even von Meister himself – Fig. 3) or collectors.

V. A Forgery?

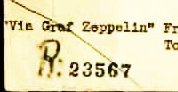

There are always people who are prepared to “dress-up” a cover, or embellish it. And a collector or even unknowing dealer then purchases/sells this “product” innocently believing it to be a genuine example. The worst is exactly when a actual, legitimate cover forms the basic of what I would call a semi-forgery. As noted at the beginning of this article, many people innocently assume that the vM#s are registry numbers. Add a spurious “R” and the deception is complete. Just such a case has been publicly documented /4/. Consider Fig. 13 and the enlarged detail in Fig. 13a.

![]() Figure 13: “Modified”

Sieger 59G offered on Ebay in 2001

Figure 13: “Modified”

Sieger 59G offered on Ebay in 2001

Figure 13a: Detail of the

“added” R for a supposed Registry

Figure 13a: Detail of the

“added” R for a supposed Registry

Such types of “penned/penciled in” registry markings are known to have occurred in Brazil, but not in this epoch in this form. There were established labels or stampers, that didn't look anything like this. If the “R:” were not there, this cover would be perfectly kosher and be a typical, run-of-the-mill 59G cover. No idea who was responsible for this little bit of embellishment, but if it has happened already once, other examples could follow and the philatelic community should be aware of this.

VI. Postscript

Since most of the records from the Pan Am flight have been lost, I'm attempting to keep a record of von Meister numbers from my own covers and those that have appeared in auction catalogs, and trying to reconstruct the original list. This endeavor could even prove very practical for such aspects as expertizing and discovering possible forgeries and/or manipulations. Anyone who has covers and wants to help, they're gladly invited to share "their numbers" with me.

References:

/*/ Expanded and unedited original manuscript for the Linn's contribution. Artur Knoth: Early Zeppelin Covers Bear von Meister Numbers; Linn's Stamp News 75(3846), 28 (July 15, 2002)

/1/ "Warum darf Graf Zeppelin keine Einschreibesendungen befördern?"; Illustriertes Briefmarkenjournal 58(13), 199 (1 July 1931 - Leipzig)

/2/ "Graf Zeppelin" Europe-Pan America Round Flight; W. Irving Glover, Second Asst. Postmaster General, 59102� (ed. 30,000)

/3/ Zeppelin Post Katalog; Sieger-Verlag, 21st Ed. (Lorch/Württemberg- Germany 1995)

/4/ 1930 BRAZIL ZEPPELIN COVER REG. 5000 RS OVPT.; Ebay Item# 1306644520 submitted on the 5th of December, 2001