|

© Dr. Artur Knoth |

Brazilian Philately: The Pan Am Zeppelin Flight of 1930 |

Brazilian Meters on the 1930 Pan Am Zeppelin Flight

I. Zeppelin Metered Mail

The 1930 Pan Am Zeppelin flight is full of „urban legends“ or in more current terms, „Internet myths“. These are sometimes brazenly used in auction descriptions to embellish and underscore that a certain item for sale is very rare and therefore deserves such an outrageous price as is being asked. Sometimes these legends have already been debunked in the literature, but unfortunately, these articles have only a very limited circulation and therefore are not readily available to the „average“, non-Zeppelin specialist, collector.

Over the years, a lot has been written concerning meters used on Zeppelin covers /1-3/. There seems to be in some people's minds a bit of confusion about the exact role of the meters. Depending upon the specific situation, one discovers that not all metered Zeppelin mail, whether totally or partially metered, was created equally. Upon looking at some examples displayed in the available literature /1-7/, one notices that in some cases the meter franking covers the whole rate, yet in some countries, the meter is supplemented by „special“ stamps (either official or „semi“-private) representing the Zeppelin and/or airmail part of the rate. Most of the problem with meter frankings was mainly due to how to do the bookkeeping for the part that LZ GmbH (Luftschiffbau Zeppelin) was to receive.

That LZ had no special problem with metered mail, is demonstrated by a small facet of Zeppelin history/9/. Figure 1 demonstrates a proposed specialized meter by the Komusina Gesellschaft (KG) that had been developed for LZ beginning in 1929. The project even got to the point of KG requesting permission of the Reichspost Ministry to fabricate and use the meter. It was a hand held device that weighed only 3 kilos (important factor for use on board) and could be rolled over a cover to either apply a meter or use the „zero“ value as a canceling device.

![]() Figure 1: An example of the meter that was being contemplated for

use by the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin Company for mail, including on

board dispatches.

Figure 1: An example of the meter that was being contemplated for

use by the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin Company for mail, including on

board dispatches.

Eventually, according to a short article that appeared in the Hamburger Fremdenblatt, LZ decided against the use of the device. LZ didn't want to deprive collectors of being able to use Zeppelin stamps on their covers (maybe that would have damped the popularity of collecting Zeppelin covers?- „There, but for the grace of God, we poor collectors went“).

II. Brazilian Zeppelin Mail - Meters

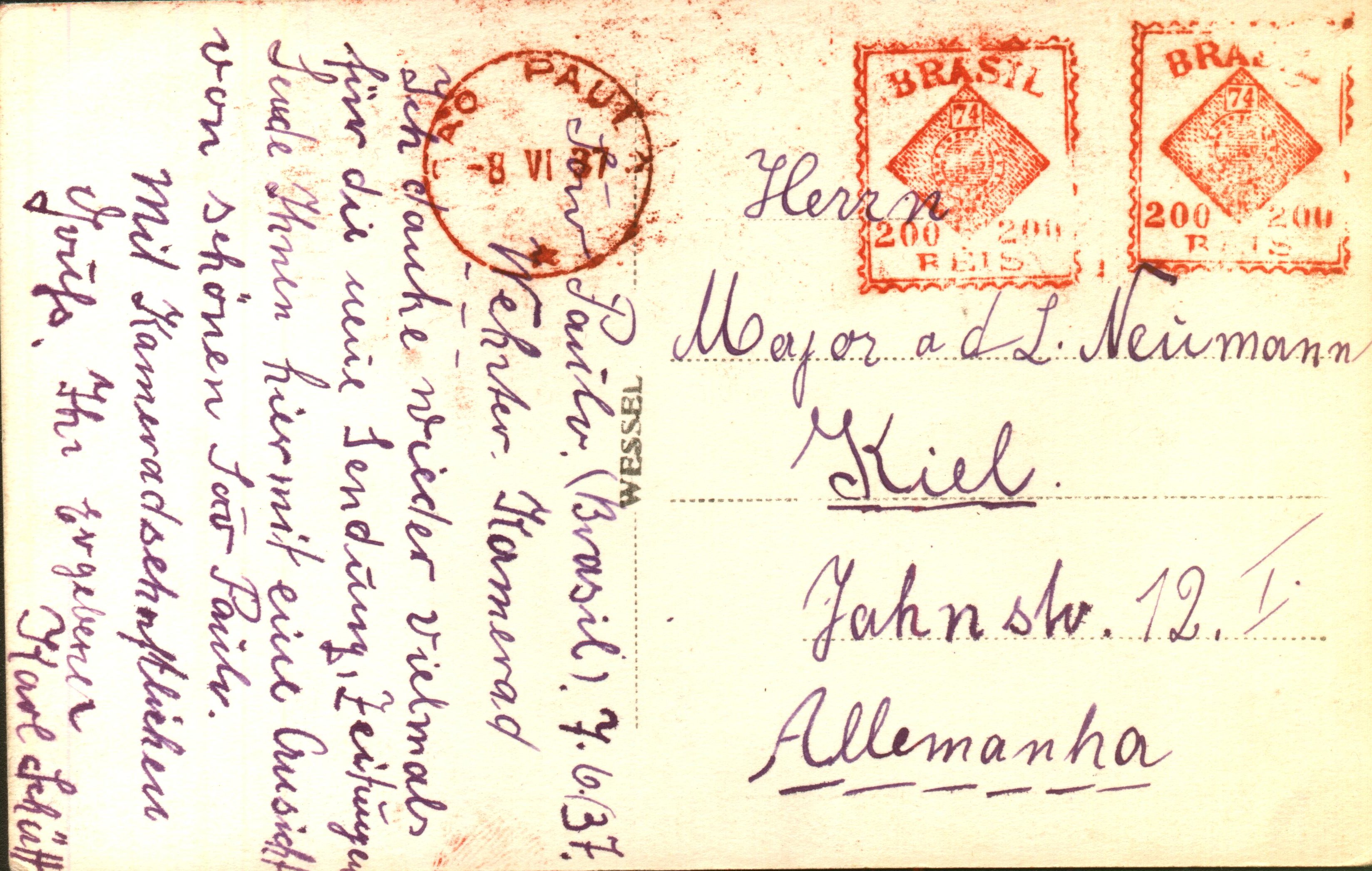

The Brazilian Zeppelin covers that have been mentioned so far /3-7/ have one thing in common, at least until about the late 30's, the postage consists of two parts. The special treatment charge, i. e. The Zeppelin part, a surcharge, was either covered by privately (1930) or special, officially issued Zeppelin/airmail stamps. The second part, the mandatory surface rate is covered with regular Brazilian stamps and/or meters. And this was exactly the case for the Pan Am flight of 1930. The meter always and only covers the mandatory Brazilian PO part of the postage and no more than that (see Fig.2).

Figure 2: Example of 1930 Pan Am Flight Brazilian cover with the

official postage covered by a BPO meter and the Zeppelin charge with

the private issue stamp.

Figure 2: Example of 1930 Pan Am Flight Brazilian cover with the

official postage covered by a BPO meter and the Zeppelin charge with

the private issue stamp.

To fully understand how, in Brazil, the use of meters on mail differed radically from other countries, leading to many misconceptions, it is useful to examine briefly the „meter“ situation in Brazil in 1930.

III. Brazilian Meters during the Zeppelin Era

The story of meters in Brazil begins in 1925 (/10-12/). Their introduction came only a handful of years before the epic Zeppelin flight in 1930. Both were novelties. In 1930, there were basically three different variations of meters being used in Brazil (the terminology used in this section is the same as in /13/). But before going into the details one needs to consider some of the background for the introduction of meters in Brazil. Brazil has a tropical/subtropical climate. Since 90% of the population lives in the coastal regions, humidity is usually very high. This made the stocking of gummed stamps a nightmare. Some stamps were even issued without gum. Each post office (even in the 1970's yet) had pots of glue that looked like they came straight out of a molasses factory. Then there's the „ferrugem“, the famous tropical stain fungus. Thus, the use of meters were a solution for this problem as well as protecting against stocks of stamps being stolen. (Not to mention the insects that the „glue dinner“ attracted constantly).

But there is another critical difference between, e. g., Brazil and the US. Whereas, at least during my childhood, US post offices had mainly a meter only at the parcel post window, and meters were used mainly by the private sector. The situation in Brazil was, and still is, quite the opposite. In Brazil meters were mainly introduced at the main post offices and as an afterthought to private users. Even today, all the post offices counters are equipped with meter machines. If you request stamps, you can get some funny looks.

Additionally, meter machines, set to a value of zero, or if postage in stamps already applied was insufficient, set to the required additional postage were used at the same time as postal cancellation devices too.

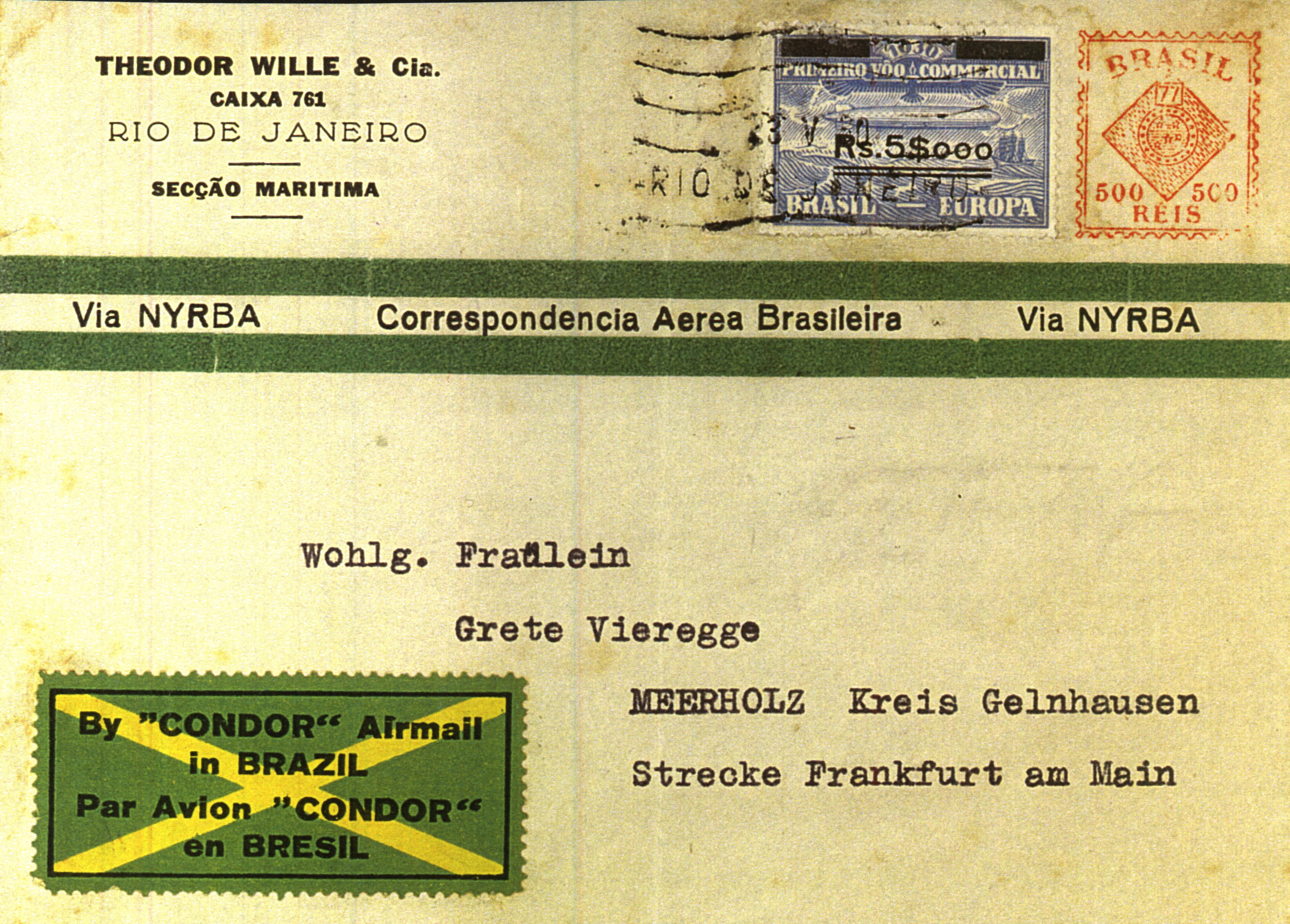

The first machines introduced in 1925 are known as the Universal NZ machines /11/. They were purchased from the Universal Postal Frankers Ltd in London; their „New Zealand“ model, i. e. Universal NZ (Fig.3) The frank consists of a lozenge shaped picture that has a small box inside the upper tip, containing a number (Fig.3a). Later, in 1929, a further model was introduced and called the „midget“. It is almost identical to the previous model except that the number contained in the lozenge has an additional „m“ ahead of it. In addition, a third meter started being used which portrays the globe used in the Brazilian Flag.

The town marks could be either lines (Fig.4c) or circular (Fig.4a and 4b). Initially, the frank was in red and the town mark was in black, to conform to the UPU rules at that time. Also the values were fixed, causing a lot of covers requiring multiple strikes for items with higher postage rates (Fig. 5 to 7).

Figure 5: Example of type of 3a+4a used as multiples to frank a

letter to Germany

Figure 5: Example of type of 3a+4a used as multiples to frank a

letter to Germany

Figure 6: Example of 3a+4c version used as multiple frank to

Germany

Figure 6: Example of 3a+4c version used as multiple frank to

Germany

Figure 7: Example of 3b multiple frank to Scotland/14/.

Figure 7: Example of 3b multiple frank to Scotland/14/.

In July 1930, the color of the town mark was changed to red to conform to the newest UPU rules (Fig. 8)/12/. Thus, theoretically, this color change rule could play an important role in any analysis of these covers.

But, as just about everything else in Brazil, there rules and then again there are rules. Thanks to a fellow collector and specialist in the meter field /15/, there are examples of meters being totally red long before the 1930 rule change. These are shown in Figures 9a and b. Both examples predate the Zeppelin Flight.

This, effectively, eliminates using the color of the town mark as a pro forma characteristic for deciding whether a cover carrying a meter is authentic or not. Only when known comparison material is available, i. e. a certain meter was known to have been using the one or other color, can definite conclusions be drawn.

IV. Meters and the Pan Am Flight

Up to now, all the metered covers for the 1930 Pan Am flight that I have seen all use a Universal NZ meter or the Globe version; as yet no „midget“ has appeared. Since all types were in use at the time of the flight, the existence an example of the latter meter on a cover is not ruled out.

The covers I've seen up to now could be put into two main categories, over (meter applied over the Zeppelin stamp) and under (meter was applied first and the subsequently applied Zeppelin stamp covers a part of the meter- usually the town mark). And then there's the question whether the cover is completely “kosher” or has something that could be considered suspicious.

The first example /16/, Fig. 10, demonstrates a case where the meter was obviously applied after the Zeppelin stamp, but never actually went on the flight. Fig. 11, a more detailed view, reinforces this conclusion, since there is no Condor cancellation applied to this cover, nor any of the further markings and cachets of this flight.

Figure 10: Meter cover without Condor cancel /16/.

Figure 10: Meter cover without Condor cancel /16/.

![]() Figure 11: Detail with 23.4.30 date /16/.

Figure 11: Detail with 23.4.30 date /16/.

Figures 10+11 do demonstrate one important fact, even if the cover didn't manage to actually travel on the flight. Machine #77 in Rio de Janeiro had a black version of the town mark during that time frame.

Figures 12+13 demonstrate a further example that actually was carried on the flight, to France /15/. The reverse of the cover (Fig. 12b) even has the Seville arrival mark typical for most covers to France. They were off-loaded in Spain and continued their travel to France from there. Only a few covers sent to Paris, made the trip to Friedrichshafen and continued on to France from there.

Figure 12: Red town mark applied over Zeppelin stamp /15/.

Figure 12: Red town mark applied over Zeppelin stamp /15/.

The main problem with the cover in Fig. 11 is the fact that in addition to the meter frank of 500 Reis, a regular Brazilian 500 Reis was added. The stamp seems to have been added after the meter, the town mark seems to continue under the stamp´s edge. Either way, the required local postage seems to have been paid twice. Furthermore, the stain appears as if a stamp had been applied and removed. All questions that can´t be easily answered.

The next example /17/ also seems to be an “echo” frank (the postage occurs twice), but here it is the meter alone that is repeated. The cover in Fig. 13 was a letter sent to the USA. In Fig.14, the enlarged detail shows that the Globe meter was actually applied twice, with the first version being almost completely applied on top of the also red Zeppelin stamp, thus making the meter next to invisible. Exactly this factor could be the reason for the double application of the meter.

Figure 14: Detail with meter on top of Zeppelin stamp /17/.

Figure 14: Detail with meter on top of Zeppelin stamp /17/.

The last “over” example is shown in Fig. 15. Here a single strike of the meter can be found. The right hand edge of the Zeppelin stamps as well as parts of the envelope show reddish smudges that are typical when envelopes were sent through these meter machines, but no second impression can be discerned.

B. Under

Here we come to an interesting aspect. If you consider the dimensions of the private Zeppelin stamps, it turns out that the height of the stamp is sufficient to mask both the circular and line town marks as shown in Fig. 4. But the width is sufficient only in the case of the circular town mark to have the stamp to completely cover the town mark. To illustrate this point consider the following graphics. First we repeat the Fig. 2 cover along side an additional version Fig. 16 /16/. In Figure 17 the detailed view demonstrates, that the circular town mark will often be visible as peeking out from under the Zeppelin stamp.

This brings us to a further, crucial consideration, whenever one sees a Brazilian metered Pan Am cover and wants to be sure of its authenticity. As demonstrated in Fig. 8 and reviewed in reference 12, theoretically there was a color change for the town mark in July 1930. Thus, if there is any remnant of the town mark, either visible or completely hidden under the zeppelin stamp, it should be black. A red town mark would be an indication of something amiss with regards to a cover´s authenticity. Yet knowing that there were many meters being used at the time in both São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro that had the town mark already red, this tool to check authenticity isn't applicable. Also, often meter were used to eliminate an impression of the town as shown on several covers exhibited here. Thus, any cover without a visible or „covered (by the stamp)“ town mark will not be necessarily questionable per se, but having a town mark helps.

The question of whether something is „kosher“ or not, is not completely trivial. My records show that up to now less than a dozen of these covers (i. e. Brazilian metered Pan Am 1930 flight) seem to exist. Here the input of my fellow philatelists would be greatly appreciated. This would make this type of cover even less numerous than the famous Sieger 59I covers, i. e. use on cover of the 5$000/1$300 overprint.

References:

/1/ Doug Kelsey: Zeppelin Airship Flights Carried Metered Mail, Linn's 71(#3660), 48 (December 21, 1998); Zeppelins Carried Mail Bearing Meter Stamps, Linn's 72(#3694), 46 (August 16, 1999)

/2/ John Duggan and Jim Graue: Commercial Zeppelin Flights to South America, (Washington 1995)

/3/ Frenge and Hagedorn: Zeppelin-Freistemplerbelege, Zeppelinpost #2, 21 (2000)

/4/ Zeppelin 4(#13), 12 (February 1990)

/5/ Zeppelin 4(#15), 9 (September 1990)

/6/ Zeppelinpost #2, 63 (1997)

/7/ Zeppelin Mail – The Ludwig Kofler Grand Prix Collection; Corinphila Auction #127, Lots# 1948,79 (May 2001)

/8/ Zeppelin 5(#2), 11 (June 2002)

/9/ Karl Hofmeister: LZ 127/Graf Zeppelin-Freistempler; Zeppelinpost #2, 26 (1998)

/10/ S.D. Barfoot and Werner Simon: Meter Postage Stamp Catalogue; Bull's Eyes 17(1), 17 (January-March 1986)

/11/ Mario Xavier Jr.: Meters in Brazil – a Brief Survey; Bull's Eyes 30(3), 17 (July-September 1999)

/12/ Wolfdietrich Wickert: Zur Geschichte der Brasilianischen Maschinen-Freistempel; ArGe Brasilien – Forschungsbericht #25, 19 (March 1986)

/13/ M.P. Bratzel Jr. and Richard Stambaugh: Cameroun: The Postage Meter Stamps; American Philatelist 117(#7)(1230), 624 (July 2003)

/14/ John Dingler private communication, many thanks for the picture file.

/15/ Rusty Morse private communication, many thanks for the picture file.

/16/ Karl-Heinz Wittig of ArGe Brasilien, private communication and many thanks for the picture files.

/17/ Gerhard Wolff and Gappe private communication and pictures.